25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism

Rendering of I-980 in Oakland as a multi-way boulevard. Credit / Dover, Kohl & Partners

The New Urbanism is a design movement toward complete, compact, connected communities—but it is also a generator of ideas that transform the landscape.

[As we go into our 30th Congress for the New Urbanism at CNU31 this week in Charlotte, NC, we are reposting this guest post originally published by Robert Steuteville on October 31, 2017 on CNU’s Public Square.]

Communities are shaped by the movement and flow of ideas, and the New Urbanism has been a particularly rich source of the currents that have directed planning and development in recent decades.

This year the 25th annual Congress for the New Urbanism was held in Seattle. The 1,400 attendees, their friends and associates and like-minded people, are like sailors on the sea of ideas that carry this movement forward.

The 25 ideas listed here offer a panoramic view of the New Urbanism, one that reaches to the horizon and beyond. Not all of these ideas were invented by New Urbanists, but new urbanists have contributed significantly to them all.

I conducted interviews with new urbanist experts on the 25 ideas, and you can find the interviews here. Now, I offer brief descriptions and thoughts.

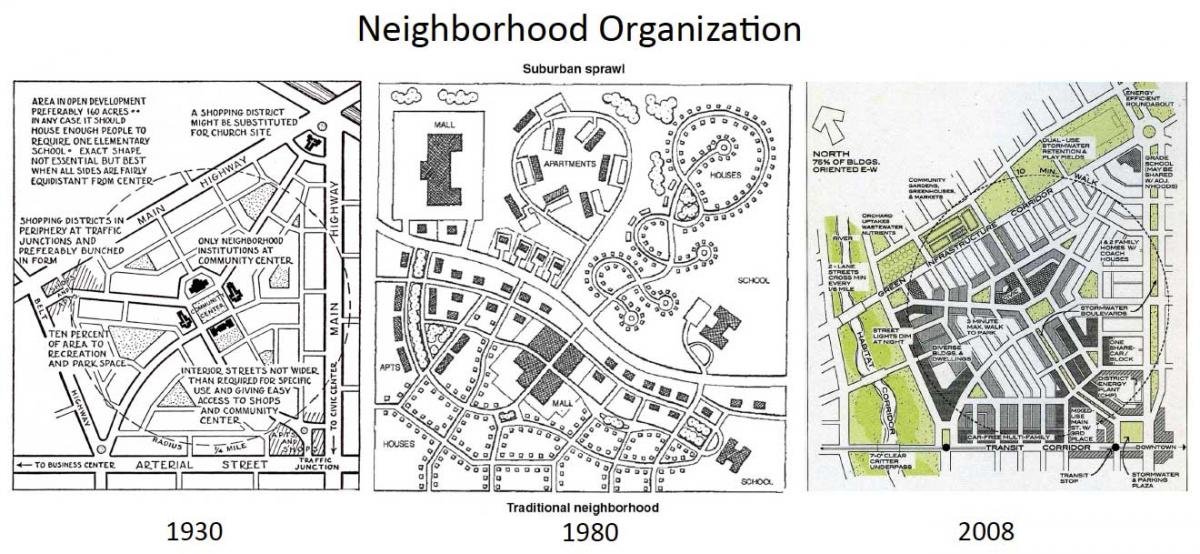

The neighborhood and the 5-minute walk are the foundation of the New Urbanism, and are now a foundation of planning in general. The concept of the walkable neighborhood seems so obvious today, it's easy to forget that 20 or 30 years ago this idea was radical. In the last half of the 20th Century, everything was built in isolated pods. I don't know how we forgot the idea of building in connected, compact, complete neighborhoods. Actually, we did not exactly forget. This concept had to be systematically unlearned through the professions, the zoning, the finance rules, and the academic institutions. Then, after 50 years, the only models we had for new development were pods and everybody who ever built a human-scale neighborhood was long gone. New Urbanists pulled the walkable neighborhood from the dustbin of history and showed that it still worked. This may be the greatest achievement of the New Urbanism. The neighborhood and the five-minute walk have become accepted and understood in planning, but they have yet to become the norm because of traffic engineering.

Perry's Neighborhood Unit (left), the new urbanist idea of traditional neighborhood compared to sprawl (center), and Doug Farr's updated Sustainable Neighborhood Unit.

The "missing middle" articulates what is missing from modern production housing, which offers single-family large-lot housing and large apartment complexes, and very little in-between. There are so many choices in between and the missing middle explores them fully—like townhouses, cottage courts, duplexes, quadriplexes, live-works, courtyard complexes, small apartment buildings and granny flats. Those choices offer livable, low-rise density in a human-scale neighborhood. The missing middle hits just the right notes, like the hook in a popular song.

Rethinking parking. Parking policies had an impact like B-52 bombers on many downtowns. In Buffalo, somebody said a few years back, "if the goal was to destroy downtown, we only halfway succeeded." That's a better job than the Germans did to London. Now, from coast to coast, more sensible parking policies are taking hold and they may be the quickest path to urban revitalization. Donald Shoup, an economist at UCLA, is a revolutionary thinker in this field.

Downtown Pasadena was revitalized through taking a different approach to parking.

Incremental development is craft beer applied to development. It is bringing back quality, local flavor, variety, and small operators to the business of real estate development. When you do that, it is easier to bring back the human-scale public realm. To the degree that your project builds a better neighborhood, you can build value and wealth as a small developer. The Incremental Development Alliance holds boot camps, because you gotta get in shape to be a small developer. Otherwise you will be eaten up by the big Jurassic developers.

The Katrina Cottage was the best idea to come out of the biggest new urban charrette ever, the Mississippi Renewal Forum, which was held six weeks after Hurricane Katrina. The Katrina Cottage is adorable, like a puppy or a kitten, but it is also incredibly useful. Nearly 4,000 were deployed as Katrina emergency housing, and they are still used today. They will probably be here 100 years from now.

Cottage Square in Ocean Springs, a grouping of Katrina Cottages. Source / Bruce Tolar

Doing the math for cities and towns. Metrics are powerful, as Chuck Marohn and Joe Minicozzi have found out. Selling urbanism is pretty easy when you "do the math." Below is the comparison between Walmart and a century-old building in downtown Asheville. Municipal fiscal health is really all about good urbanism.

Comparison of Taxes Generated Per Acre of two different development patterns. Source / Urban3

Tactical Urbanism is the guerilla warfare of the New Urbanism. There is no way to beat the departments of transportation with standard warfare. If you line up against them, you may win a battle, but you will lose the war, and the casualties will be high. The Tactical Urbanists have figured out that by using quick, tactical methods, you can be in and out and change public opinion before the DOTs have a chance to react.

Mixed-use urban centers. Why build a shopping center or "office park," an oxymoron, when you could build a town center or an urban center? Life is more than shopping. Some may find that hard to believe, but it is true. And businesses all over America are flocking to mixed-use urban centers, because that's where workers want to be. They don't want to be imprisoned in office parks for half of their waking lives.

Suburban retrofit. The vast majority of our metro areas are suburban, and much of its is drive-only suburban. As the suburbs age, they can be given new life through retrofit. Retrofit is the suburban fountain of youth. It can literally save the suburbs. Conventional suburbs, conceived in the mid-20th Century, are outdated. The oldest suburbs, the mixed-use walkable kind, are the most current—they meet market demand. Companies don't want to locate in isolated places. Many shopping malls and shopping centers are dying, and suburban retrofit is the answer. We invested trillions of dollars in the suburbs, and some believe this investment has no future. I believe that significant value that can be salvaged with retrofit. This is a sunk cost opportunity, not dilemma. At CNU, we call this Build a Better Burb.

Traditional neighborhood development. Why produce a high-quality private realm and low-quality public realm? Why step out of your yard and confront the harsh, stressful environment of garage-scapes and cars? Instead, build a neighborhood or a town. This is an honorable and age-old practice, updated by TND.

Atlanta’s Glenwood Park is the result of re-envisioning 28 acres into a sustainable, walkable traditional neighborhood. Image Credit / Urbanism Visualized

Architecture that puts the city first. Too much architecture is about competing for attention: Architecture as sculptural object. But the best architecture is like a symphony, it works with everything around it to create beautiful music. Part of that music is the spaces in between buildings, because that's where people meet in a city or town. That's the public realm. Architecture has a duty to make the public realm better. That can be as simple as placing a porch in front instead of a garage door. This has been a key goal of new urbanist architecture—make the public realm better.

Form-based codes rewrite the DNA of communities. Since the middle of the 20th Century, zoning has been a force toward sprawling suburbs and disinvestment of historic cities and towns. New urbanists created urban design codes called form-based codes to physically define streets and public spaces as places of shared use, and to build complete neighborhoods. Form-based codes have been adopted in hundreds of cities and towns in the US and abroad as alternatives to conventional zoning.

Lean Urbanism seeks to bring common sense back to planning and development—because great neighborhoods are built with many hands, often in small pieces. This movement pushes the envelope to make it easier to build great places and for small players to get in the game.

Light Imprint, or "green infrastructure." With infrastructure and asphalt, less is more. Light imprint is about building a neighborhood lightly on the land, allowing as much rain to filter directly into the ground as possible. This is like "pollution prevention" for New Urbanism.

Context-based street design. Streets are the bones of a community, and bones are designed according to where they are in the body. Imagine if you had a femur on your finger. It would not work well. Similarly, the streets must be designed according to what is around them, and the activities that are needed and desired. That's what context-based street design is all about. If a street is primarily designed to move cars, it won't support social connections, small businesses, walking, or many of the other vital aspects of community life. In cities or towns, streets are public space.

Colorado Avenue in Stuart, Florida. The desired target speed is achieved by using a combination of tools—a raised crossing, curb extensions, inset parking, trees and ground cover—all used to slow traffic as the road approaches a key intersection to enter the quaint downtown.

The public realm. This is where anyone can go, where anyone is welcome, where people meet, and where much of the business of the city or town takes place. The whole is much, much greater than the sum of the parts. The public realm includes streets and public spaces. New urbanists tend to enclose these spaces with buildings. The buildings are walls of outdoor rooms, and people feel comfortable in rooms. Former Bogota mayor Enrique Peñalosa described the joyful effect of the public realm at its best: “Great public space is a kind of magical good. It never ceases to yield happiness. It is almost happiness itself.”

The Charter of the New Urbanism is the movement's solid intellectual foundation. The Charter's principles have withstood the test of time and empirical research, and they can be implemented in countless ways.

The rural-to-urban transect is a diagram that brilliantly organizes the built and natural environments so that the human habitat can be analyzed and understood as a continuum with the natural world. The Transect teaches us that, as sprawl is a monoculture, traditional urbanism is an ecosystem—just like nature. The Transect is a vital concept for form-based design and coding.

A version of the original Transect diagram, with six successional zones from nature to urban core, with special district. Image Credit / DPZ CoDesign.

Transit-oriented development. Unifying land use and transportation is the Holy Grail of urban planning. More and more, cities and towns have been seeking that Holy Grail through transit-oriented development. As much sense as this concept makes, it was relatively rare until 15 years ago. New urbanists have been instrumental to bringing it back.

Street networks. The paradox about streets is that in order to get good ones, you have to think beyond any single street. The City is not a Tree, as Christopher Alexander wrote, it is a connected network of streets. The idea is at the heart of New Urbanism.

The charrette. To get a complete neighborhood or community you need a complete process, and that is the charrette. At its best, it brings all of the stakeholders together at all levels in a holistic process. It compresses the design time so that decisions are made and competing interests can be resolved under deadline pressure. Charrettes focus the mind.

Sustainable urbanism is woven into the fabric of New Urbanism. A few decades ago those two words would have been considered oxymoronic. No longer. The New Urbanism provides key tools for environmentalists and sustainability advocates.

South Main in Buena Vista, CO, is a 41 acre site of a former garbage dump transformed by siblings Jed and Katie Selby into a walkable community facing the Arkansas River in the Colorado Rockies. Image Credit / Urbanism Visualized

Public housing that engages the city. In the late 20th Century, much of the public housing in the US was a mess—routinely built in the form of "projects" that were symbols of crime-ridden, decaying cities. HUD leadership took the principles of new urban neighborhoods and applied them with the transformative HOPE VI program, which changed the face of public housing. These principles became standard for later federal programs like Choice Neighborhoods and similar initiatives in cities.

The polycentric region is the superstructure of good urbanism. The idea envisions and supports all community and place types such as hamlet, village, town, neighborhood, and city—ideally linked to transit. The polycentric region connects farm to table, nature to urban core, home to workplace, and enables people to navigate from town to city, and from neighborhood to neighborhood.

Freeways without futures—a decade-long campaign by CNU—has been at the vanguard of removing unnecessary freeways from cities. Ramming freeways through city neighborhoods did astronomical damage to cities in the 20th Century. While many of these freeways are probably here to stay, others could be removed and replaced with surface streets. Every time this has happened, whether in San Francisco, New York City, Rochester, Milwaukee, or Seoul, Korea, the city always has gotten better.

That concludes my brief descriptions of Great Ideas of the New Urbanism. These ideas continue to have a profound impact on the US and beyond, and new ideas emerge all of the time, dealing with issues like climate change, finance reform, equity, and suburban poverty.

Here is a link to download all of the 25 Great Ideas in a draft version of a book.